Bad Program

It's been a while again. A while since I left a weird, wander-y post about pain wizards and how you should back up your hard drives. A while since that was something important to write about. A Josh in 2013 might have expected a Josh in 2020 to have an eyepatch and wear leather armor best suited to fend off the nightly water raiders. As a 2020 Josh, I'm not sure how to explain that I don't wear an eyepatch or leather, but frankly, it'd make more sense if I did.

It's been seven years since I wrote here. It's been six years since I helped make videos and run tech stuff for a local improv troupe. Four years since I helped to release a book. Four months since I helped to release another book. A couple of percentage points increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide, and half a degree increase in average global temperature. And three months since we've been working from home during COVID-19 global pandemic. A few weeks of protests and riots against police brutality and systemic racism.

The eyepatch doesn't feel far off.

Years ago, I used to be able to hear the chirping of electrical components inside of my computer. In between the gentle whir of the chassis fans and the whine of the spinning platter drive, I could hear a tiny, high-pitched chorus of beeps emitted by overheated capacitors and radio transmitters.

Among possible superpowers, it's one of the lamest. Even if I could somehow distinguish between the millions or billions of individual ones and zeroes flying past every second, there's no way I could tell what was being done or said. Humans just aren't wired for that. Unless the hard drive was giving off the grinding, angry clicks of imminent failure, all that I could determine was that the computer was a) powered on, and b) doing something.

I started to lose my lame superpower in the years after college. It might have been that I attended too many concerts while (naively) not wearing hearing protection. Or that I fired too many bullets while (idiotically) not wearing hearing protection. Or that I suffered inner-ear barotrauma after I (irresponsibly) got on a plane while very sick and had fluid in my ears. I remember sitting in my apartment in my early twenties, laptop held up to my head. I could still hear the tiny chirping of computer components in my right ear. But they were gone in my left.

I get by just fine nowadays. But there's a difference between left and right. And it's truly frustrating at times to have such a disparity. I can lay in bed on one side and hear the road noise from the highway, the cars and motorcycles coming and going. Then if I turn over, I hear different noises. Noises that are harder to distinguish and identify. The house shifting? A magpie hopping down the slope of a roof? The neighbors arguing on their back deck? The heating system pumps failing?

I'm sure it's the same motorcycle speeding back and forth over the overpass. The same mid-2000's exhaust package revving at the stoplight. The same trucks engine braking down the hill. But that doesn't help me get to sleep. I want to know that it's something innocuous. Something I don't need to be awake for, aware of. But I have to work so much harder. I have to pay attention just so I don't have to pay attention.

Last summer (2019), construction at the airport sent cargo planes over our house every 20 minutes. To sleep, I started to wear earplugs at night. But even when the construction completed this winter, and the planes stopped, I kept wearing them. It's easier to sleep in total silence than it is to hear half of everything.

The first computer I bought was disappointing.

It was a desktop tower draped in a classic early-2000's beige. The Internet was happening, but Blackberries and iPhones were still years away. Computing power was becoming cheaper, but nothing but Gameboys and Game Gears were designed to run on batteries. Everything worth its silicon required a power cord and dimmed the lights a bit when you turned it on. And if it had a fan, it sounded like a goddamned jet engine taking off.

I had a few hundred dollars saved up from Christmases, birthdays, chores, and lawn mowing. Gaming magazines repeatedly informed me that you didn't have to break the bank to take your gaming to the next level. Of course, I wanted to take my gaming to the next level. I wanted to know what it was like to play Quake 3 on higher graphical settings than 'low'.

"I've done some research," I told my (probably disinterested) parents. My friends had long since had Nintendo 64s and Playstations that played games beautifully, with high polygon counts and crisp framerates. I understood that videogame consoles tended to run smoothly because they were programmed specifically for their gaming hardware. "But ultimately," I explained to my (no longer listening) parents, "game consoles were limited because one could not upgrade hardware in the same way you can upgrade a computer. PC gaming was a smarter investment," I concluded, "and consoles would adopt a similar model of hardware upgradeability to PCs in the near future."

Hundreds of dollars and hours later, I was playing Quake 3 at a resolution of 1600x1200 pixels with a graphics setting of 'high'. Which was pretty great. I'd never seen so many pixels. Such texture. Such bump mapping. The fan roared from the moment my gaming rig turned on until 45 minutes later when I beat Quake 3 because it had a really disappointingly short single-player mode.

It went downhill from there.

The CPU I bought was about the cheapest that was available on the market. Reading up on it some years later, I learned that the Celeron class of chips were essentially the same chips as their more expensive siblings, but with certain performance features disabled. Intel's reasoning was that they didn't want to spend the extra money to retool their manufacturing process just for cheaper chips, but they did want to compete with their cheaper competitors. They could stand to lose a little on a chip, but their competitors couldn't stand to lose a whole sale.

Following the poor CPU performance, there were the weekly catastrophic system failures. Even though Microsoft assured its customers that all drivers for Windows 98 were tested thoroughly before being delivered, it didn't mean that they necessarily tested the drivers in concert with each other. I was never able to track down the exact conflict (I was only 15), but I was certain that the video card and the audio card were fighting with each other. When that happened, Windows would get confused, and write garbage to the hard drives. When this happened, I would have to reinstall the system from scratch.

Where Playstations and N64s almost never fail, and would run until the heat death of the universe, my bargain basement custom PC would fail if you looked at it funny. And it still cost hundreds of dollars more than the videogame consoles.

Through disappointment, lessons were learned.

First, that you should always have good backups, especially when you have a few hundred hours on your Baldur's Gate saves (don't worry, it's been seven years, but I haven't stopped harping on this).

Second, that PC gaming is for the wealthy and patient.

Third, and more perplexing at the time, is that there was so much more to a game than how much hardware you could throw at it.

If I'd had thousands of dollars more, I could have bought a dream computer with components that were certified and verified to work together. Maybe then the games would run perfectly. But I didn't have thousands more. I had spent all I had. And there were only so many lawns I could mow.

I would get frustrated. I would go over to my friends' places and watch them play. Somehow, videogame console developers could get their games to do exactly what they wanted and make it look smooth and beautiful, all with hardware that was objectively inferior, and wouldn't be upgraded for the life of the platform.

I wondered at the time if something else was going on.

Equally distressing about hearing loss is the worsening of my directional hearing.

Much in the same way that two eyes give us depth perception, two ears give us stereo hearing and being able to tell where a sound came from. But with one ear out of tune, it's more difficult. Some frequencies and volumes are easy to locate. For other sounds, especially those beneath the hearing threshold of my left ear, my brain just shrugs. I have to swing around with my good ear, hoping the sound repeats enough times for me to find it.

Two years ago, I had my ears checked out at a clinic. I told them my theories about my hearing loss. They shrugged a maybe and asked instead if I had a family history of hearing loss. I told them stories about my grandfather being able to distinguish between subtle engine noises for the planes he worked on in the Air Force. They asked if anyone in my family wore hearing aids. I said yes, all of my grandparents (including my grandfather later in life). They said I should keep an eye on my hearing, and that if it got any worse, I could potentially be a candidate for hearing aids.

I get by just fine. It probably sucks that I'm whining about what I've got. It's something I can deal with. I have to pay a little more attention to objects in the room, remembering where they are, what sounds they make. I do pretty well. But it does take some extra effort.

One thing I've noticed is that I startle a lot easier. Where once I could effortlessly track direction and distance for many sounds, now I'm surprised a lot more often. At work, my screens used to face out of my cubicle, which meant that visitors would approach me from behind. If I was particularly focused on something, the "Hello" from behind would be enough to make me jump. This, of course, was a delightfully entertaining game for my coworkers to play.

I got better at listening for doors opening and loud footsteps so I wouldn't startle, but this meant that I was having to pay more attention to the environment, and less to what I was doing. If I was stressed, or under-slept, it was harder to pay attention at all, much less be able to swing attention between my work and my environment.

My new work laptop was disappointing.

It wasn't the highest of high end, but it was still up there. It had more processors, more memory, hell, even a wireless card that I couldn't have dreamed of almost 20 years ago when I'd bought my first computer.

No, it was disappointing because I could hear the computer. In such an advanced age where computers are no longer beige boxes, but silent, beautiful black rectangles, I could once again hear the computer. Even despite my hearing loss, I could hear the computer. Nowadays, a loud fan is the sound of overwork, of inefficiency, of malfunction. And my laptop's chassis fan always ran at full blast like I was asking it to simulate the center of a black hole.

I looked at my diagnostic tools. I found a busy Windows process called Offline Files whose demure purpose was to make my personal files available whenever my laptop disconnected from the network. Being a laptop that I could connect and disconnect at will, this seemed to make a lot of sense.

Except it didn't make any sense. I had the Offline Files process running on my old workstation, and it didn't cause problems. The process was supposed to run in the background, quietly and discreetly synchronize my files, then fade into the ether without any harm done. Instead, it leeched 25% of my processing power from the time I logged in to the time I shut down the computer.

After some painstaking, lengthy investigation I found what caused it. Or rather, the multiple contributing factors that when taken separately were not an issue, but together, caused my fan to keep a coffee cup warm if I put it next to my laptop.

The first factor was that I had more than 3 million files stored under my profile. You might say, "Well. Why are you complaining, Josh? That's too many files." To which I would say, "Sure, it's a lot, but that's my job, and storing files is what computers are good at." Depending on the project, each application might contain 10,000+ component files that need to be present on the filesystem in order to compile, render, or test. But even with that many files, I wasn't using them all at once. For the most part they just sat there until I searched or compiled them into something else.

The second factor was that I took my laptop home at night. With my old workstation it would remain powered on overnight after I left. But with my laptop it would be suspended, put in a backpack, and taken home with me in case I needed to work from home (which seemed a remote possibility at the time). Normally, this suspension would pause all running processes, causing any active jobs or network connections to quit or time out. This was not usually an issue, as most software has the ability to gracefully recover from failure.

But not the Offline Files process. It would attempt to synchronize all 3 million files. And over the span of a 9 hour day, it would only get through a portion of the files (say, 2 million). When I would suspend the laptop in the evening the Offline Files would stop, record where it had finished, and patiently wait for the next time it was booted and connected to the network.

Here's where things fell apart. The next morning, my laptop would wake up as I pulled it out of my backpack and started my day. It would remember that it had only completed 2 out of the 3 million files, and needed to finish its work. As a precaution, it would quickly check the synchronized files to see if there were any changes. Among 2 million files, the odds were good that it would find some changes, and decide that rather than proceeding to complete the last million, it instead needed to synchronize all files in order to determine the nature of the conflict. It would start over again, even though it would never be able to complete 3 million files in a 9 hour period.

My old workstation didn't have a problem because it was always connected. Millions of files? No problem. It might take days or weeks, but it was never shut off or suspended so it would just finish up everything eventually. Even though it was probably only half as powerful as my new laptop, it felt a lot more responsive. Mostly because it wasn't continuously trying to process 3 million files, and was free to do other tasks than pushing its 3 million boulders up a mountain.

I could get by. The laptop was slow, but it was still working, and an annoyingly loud fan was pretty low in the priority list. I had programs to write, problems to solve. So in between everything, I kept looking. It took me years to isolate my problem. Years of Googling. Years of having no idea what was wrong. Talking with my colleagues. My colleagues having no idea what was wrong. More desperate searching. All in hopes of narrowing the infinite realm of improbability and leaving only the possible.

Once I found the problem, I moved my millions of files elsewhere, reducing the size of my profile to less than 10,000 files. The next morning, my chassis fan still ran for a while. But a quarter-hour later, the fan stopped.

I was elated. It was fantastic. I had solved the problem. Instead of just hearing the fan all the time, I could actually hear the difference between when it was busy and when it was not. It was a small thing, but it felt huge. I wouldn't have to wait the full seven years for the next company-wide hardware refresh listening to an angry fan before my laptop got replaced.

The victory was short-lived. We soon implemented new programs, and all gains were lost.

One program was an inventory and software cataloging agent, whose job was to scan your computer and report back any and all software it found. Its behavior was to wait until the machine was detected to be idle, then perform a deep scan of all files, eating 10-15% of system resources while doing so. The process would take 1-3 hours after every login.

One was a log capture tool that was initially misconfigured, and would continuously scan the hard drive for any files ending with ".log" and eat 5-10% of resources.

One was a permission escalation tool that would allow us to dole out the right to run certain programs without having to grant full admin capability to machines. Its job was to sit in front of every program execution, scan the program, and decide whether the permissions required met with our company policy. Given that this program had to run ahead of every other program, it added a 2-5 second delay to every time we ran a program. If you had to run a program thousands of times, throughput would slow to a crawl.

But the worst was the new security software. Installed in a rush following worries about hackers encrypting our data and ransoming it back to us, it was deployed company-wide with minimal testing, and with all of its knobs turned up to the max. Similar to the escalation tool, it also scans every executable, fingerprinting it and querying a central server to ask if the program is known to be bad. It then goes beyond, scanning on incoming and outgoing network traffic, all file reads and writes, and all interaction between user processes and the operating system (system calls). Its "security forensics" feature eats 10-15% of resources while scanning, which can take hours. It also has a glass jaw when it comes to scanning. Like Offline Files before it, if I suspend in the middle of a scan, it starts over.

I'm sure all of these programs worked great in a lab somewhere. Isolated. Barely noticeable, especially when running on brand new hardware. But when slapped together, barely tested, and bought because an industry magazine told us you didn't have to break the bank to secure your corporate network, my little laptop's fan just spins and spins.

It's hard to say what makes a good program. Certainly its design and construction, how well-made it is, whether it eats 25% of system resources for no good reason. Also the experience of the user, the look and feel, the feelings it invokes. But also its longevity. Whether it remains timeless.

By the time I was out of school, computers were just fast enough that they could emulate game consoles. This meant that rather than having to purchase older game hardware, I could instead simulate it, creating a virtual game console in my computer that was able to perfectly and in real time simulate the games of yesteryear. This was particularly great for me. Being older, I could appreciate the quality of a game without being obsessed with whether the graphic settings were at maximum. And I could finally play the classic gaming and cultural touchstones I'd missed out on by fighting on the wrong side of the videogame console wars.

Within a few years, computers were fast enough that they could simulate themselves at near-native speeds. Virtualization, paravirtualization, application virtual machines and containerization are now the norm, with each layer of simulation providing for added levels of security, reliability, portability, maintainability, and so on. If you've accessed a popular website in the last 5 years, you have been more than likely talking to a dream of a computer program, ran by the dream of an operating system, ran by a dream of a computer.

There are inefficiencies, of course. With all of these layers, the computational performance is worse. But as computers become faster, and hardware and computation become cheaper, it's far more economical to simply acquire more hardware to make up for the difference. If you're only able to get 80% of your usual speed, you can just buy twice the hardware and improve performance overall. Save for a few select use cases and industries, it's no longer cost-effective to spend money to make computer programs more efficient.

That's why one of my favorite things to watch on Youtube is an early videogame console programmer talking about how he accomplished amazing things using aging, limited, and seemingly primitive game console hardware. In short 5-10 minute videos, he details the challenges, his insights and experience, followed by a demonstration of the completed graphical and audio effects that were seemingly impossible on the consoles of the day.

It is delightful. The channel makes me feel awe for the art that came from such adversity. It answers my question from twenty years ago on why my PC was garbage, and consoles played well. I was too young to appreciate all that went into the games of the time. That people, some decades later, go through the trouble to emulate the games he and others like him made is a testament to their achievement.

The channel also leaves me with a feeling of awful, bottomless dread. Dread that in my years of programming I have created nothing as artful. Dread that in my career, I may never create anything as clever. Nothing more interesting than spreadsheet importers. Data migrators. Form inputs, PDFs outputs. Small programs that solve small problems that have all been solved better before. Dread that the things I create are expendable. Replaceable. Forgettable. That the considerable time I put towards them was a waste of life.

There was a time that I might have made the argument that a good program is one you'll want to run in twenty years. One that, like a beloved ancient videogame, is worth the effort of trying to emulate using your staggeringly powerful future supercomputer.

But that argument doesn't make sense anymore. Nowadays, everything is emulated, virtualized, simulated by design. Everything lives on highly-redundant hardware, somewhere in the cloud, that can no longer break even if it wants to. Even the bad programs will run until the power goes out, or until the heat death of the universe, whichever comes first.

I think that good programs are ones that we'll still be running in twenty, thirty, forty years, even knowing that they were put together by flawed yet artful human beings.

I think that eventually computers won't require human beings to tell them what to do. So long as hardware keeps getting faster and cheaper, eventually it'll be more cost-effective and more reliable to have machine learning and artificial intelligences write programs for us. It will take more CPU, more memory, more power and resources, but that won't matter.

Good programs will be those that can't be replaced by AI-generated programs. Bad programs will be those that can be replaced.

That is assuming that hardware keeps getting faster and cheaper.

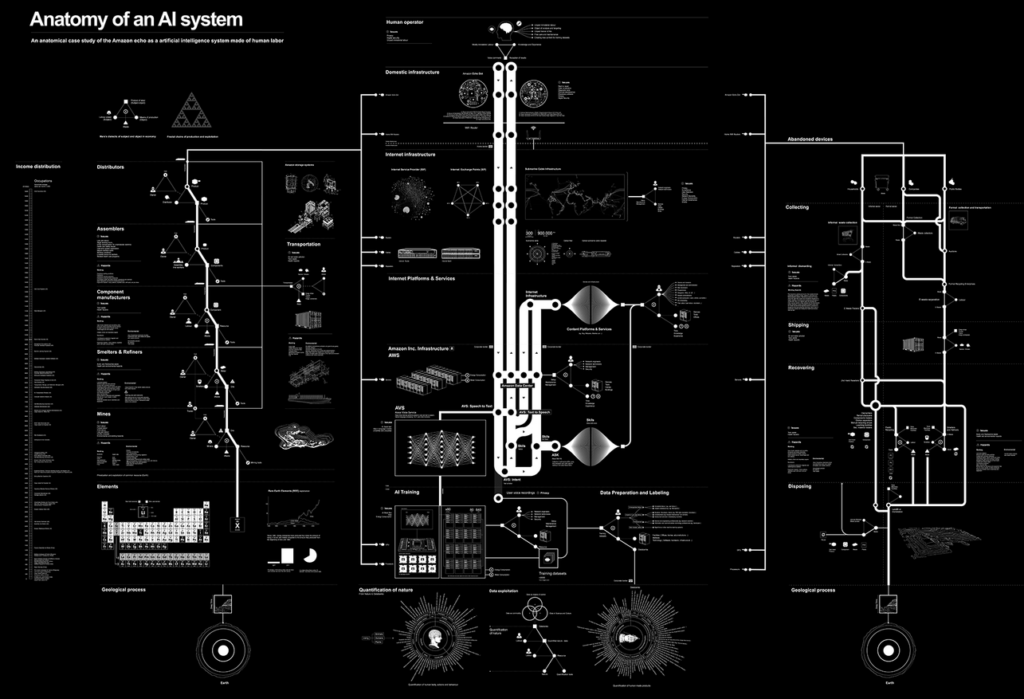

A while ago I found Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler's Anatomy of an AI System.

Their analysis walks through the parts and pieces of modern artificial intelligence, capturing not only the software and logical components all the way down to its raw physical elements, labor force, and supply chain.

It shows what is required to have an Alexa in your home. It also shows the unfathomable resource requirements of a global-scale software implementation. It was beautiful, in a way. But the pieces together are terrifying.

Through their essays, they show that almost every aspect of the AI is a form of extraction and exploitation. From the mineworkers, to the electronics and hardware assembly workers, all the way through to the computer programmers, even the power companies, the story is the same: find the cheapest possible labor and materials in order to extract and amass the greatest wealth, even if it's at the cost of human lives and dignity. Such is capitalism.

It's easy to condemn a megacorporation. Easy to punch up. But then I considered every piece of electronics I had ever bought. Or inherited. Which in my case is fairly easy because I have never thrown away a computer. I can look at all of them by walking into my office. I can tell you where I got them, why I bought them, which gaming magazine said what about the video card, what was interesting or rare about it, the quirks, and in some sad cases, why they ultimately stopped working. I can tell you about the games I played on them, the software and stories I wrote on them, and the technical and nostalgic reasons I might want to keep the old hardware around.

But I know with absolute certainty that none of them were purchased while keeping in mind the well-being of those that assembled them. Or that programmed them. Or dug their material components out of the ground.

I thought about the data centers, the huge, climate-controlled rooms filled with racks of computers and the roar of HVAC systems trying to stay ahead of the heat of a few tons of hot silicon. I thought about the 32 terrawatt-hours of electricity spent in 2017 just for the purpose of mining bitcoin. I thought about Amazon, and Google, and Microsoft, and all of the other companies reselling their computer hardware "in the cloud" so that Netflixes, Hulus, and Facebooks can be removed from having to hear the fans going full blast while their software eats up more and more computing resources. While their power plant pumps out more carbon dioxide and heat. While they extract and exploit our data.

Since last we spoke, a lot has happened.

It's hard to account for all that time. It's easiest just to confirm that I'm getting older, and all of the rights, privileges, and honors thereunto appertaining. I care about putting money into a Roth IRA now. I'm not especially proud of my silly spreadsheet importers and data migrators, but they helped me pay off my mortgage. Before COVID-19 I was going to the gym regularly. I even ran twelve miles last weekend. Contiguous miles, even.

But my successes and achievements can only be weighed against those who did better, or those who never even had the same opportunity. It's hard to feel exceptional when you know you are anything but that. It's hard to feel like you struggle when you know you do anything but that. The more I learn about the world and its people the more culpable I feel. The harder it is to log in and work on code that harasses people when they are late on their bill, or determines whether or not their power should be shut off in the dead of winter. The harder it is to forget that I wouldn't have a job if someone, somewhere else wasn't being paid a dollar a day to dig up cobalt and conductors for a laptop I'll just complain about. The harder it is to focus on any of the successes and not entirely on the failures.

In the last few months I've been having depressive episodes and bouts of anxiety. It's hard to explain why. My usual models are inadequate. You can't quite equate an overworked computer, burdened with bad programs, to the feeling of an anxious mind. But if you squint, they might share a shape, some edges. And if either had a sound, they would sound like the fan of a computer that you can't get to shut off. A sound you hear but you can't tell where it's coming from no matter which direction you turn your head.

I've struggled with these types of things in the past. I know they come and go. I'm aware of it happening, often during, but sometimes only just after. I'm enough of a diagnostician to try to isolate, test, record findings, analyze results. The precipitating factors are known, but unfortunately common and pervasive. The factors have always been there, though maybe there were fewer of these factors in years past. Maybe it used to be easier to decide what factors to pay attention to and which to ignore. Or maybe I just don't have the option to ignore any of them anymore. Maybe now I can't finish processing them all before I suspend for the night.

I have a few coping mechanisms that are helpful. One is videogames, using them to distract and take focus long enough for whatever is happening to go away. Animal Crossing is my jam, as it is for so many my age, race, and economic class. At time of writing I've put 70 hours in, most of which is just buying and decorating my island with garden gnomes. Which feels indulgent and privileged, knowing the game is about making your world a better place by amassing enough wealth. But it still helps.

Another way to cope is through work, a place where I'm necessary and capable and able to (sometimes) make things that are creatively fulfilling and objectively useful. Working from home has been a considerable improvement, even though the circumstances are extraordinary, grim, and likely temporary. There are fewer people who find humor in my startling (though I will note, that number of people is still not zero while at home). But it's still hard to work in the industry knowing what I'm complicit in, a party to, benefitting from, even in ignorance. But still. It helps.

Friends and family and loved ones help. But it's hard to be on a video call when you can't tell which direction they're speaking from. It's hard to know they're far away. It's hard to remember when you've failed them and nothing else. But if I can bring myself to log in, it helps.

Writing used to help. I used to write a lot. Since we last spoke? I'd written quite a bit (though elsewhere). Now I barely write anymore. Writing somehow became a precipitating factor. I had to quit working on Skysail after seven years. Even just this blog entry has taken me three weeks to write. Every time I come back, it feels like I have to start all over again. Begin anew to scan the 3 million things that I should be writing about, could be writing about.

It's hard to write with everything that is falling apart. Hard to write during a global pandemic. Hard to write while there are protests against police brutality. Hard to write while there is police brutality. Systemic racism. Mass incarceration. Rape culture and sexism. White supremacy and fascism. Hard to write knowing that if the world needed to hear my voice, the time is not now, if it ever was.

But since we last spoke, it had been too long.

Perhaps in another seven years we can review this. See how well everything turns out. I hope we can prolong the eyepatch. It's weird enough only having one good ear.

- Previous: Pain Wizards

- Next: Everything Old Is You Again