We're not all so bad

I've been thinking about women and the computer science field, lately. And not in the perverted, lonely way you probably think.

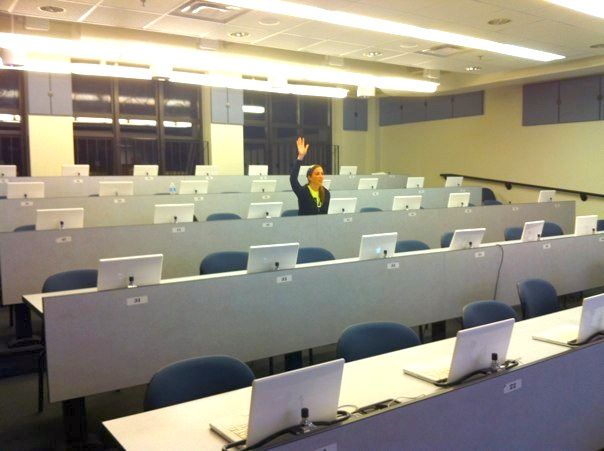

Source: reddit.com, "What I feel like as a girl in Computer Science?"

I was reading this about a week ago, which was interesting because it brought to light again something that had been a curiosity to me in the last few years. That thing being: the IT and software development fields have only just recently (in the last 20 years) been male-dominated career paths. Before the 90's, women were represented in computer-related fields pretty strongly among the sciences, and programming and the like were actually marketed directly to women as being exciting and rewarding fields. Though not necessarily given much credit due to extreme workplace inequality (my Grandmother recalls in the 1960's being told not to touch the computers because women's hairspray interfered with the equipment), recent studies and documentaries show how female programmers and computer scientists were critical in the success of some of the most famous early examples of computers and computing.

I find this interesting for an additional reason: computer programming and related fields, until the late 80's, were paid considerably less than other engineering/technical type professions. Programming, when it was still considered the tedious tasks of flipping switches or shuffling punch cards, was thought of as a menial, clerical-type job. Depending on the application, it may have been just that: feeding in simple data to simple programs so that somebody didn't have to do the calculations by hand. But even that still required pretty intimate knowledge of the system, how to use it, and how to fix things when they inevitably went wrong.

---

Probably about 10 years ago, I was asking my father computer questions. Phrasing it like that, though, is probably poor, as it implies that there was a time I wasn't asking my father computer questions. At that point, I was pretty well on my way to learning early computer programming, having created my first few web sites, my prototype for the original idkfa, and I was heavily involved in the IT department in my high school, helping teachers with their email and stringing wires.

At that point, I was asking my father about Linux, something I'd heard about reading about programming on the Internet. My father, after struggling a little bit to remember the cryptic commands and syntax through years of personal disuse, told me, with a resigned and joking tone: "Linux is an oral tradition."

Thinking back on that years later, it's sort of an interesting statement, and one that is true, probably less specifically about Linux, but computer literacy in general.

The "oral tradition" he was referring to was the seemingly opaque nature of Linux and Unix systems, the incredibly steep and high learning curve for memorizing cryptic commands, file structures, and initialization sequences, for being dumped off the bat into a system that in response to typing "help," it prints out a detailed specification of the current scripting language engine / kernel shell you're running. Unless you're very smart, or very lucky, it takes somebody actively telling or showing you how to interact with a Unix system to get an idea of how it is *supposed* to work.

The same goes for systems like Windows and Mac OS. Given your first time working with the interfaces, you might not know which button to use to run applications, to communicate, to send email, to shut down the computer. You might not know it's possible to copy items into memory and then paste them elsewhere. You might not know that there is a key combination to do just that. You might not know that there are key combinations to begin with, or how or why to "right click," or minimize a program, that is, unless you read about it, was told about it, or was shown by somebody else.

I've said at various times that reading somebody else's programming code is like reading how they think. I feel, to some degree, that seeing somebody interact with computers at a more basic level still reflects this, even if it's just to see how somebody learned. Or rather, how the tradition of using a computer was passed from one person to the next. I wonder what bizarre traditions I pass on to others, and whether in the future they'll be useful and efficient, or archaic and obsolete

---

The pay disparity for early computer programmers (men and women) was probably compounded by the fact that, as a profession, working with computers was new, and mostly misunderstood, and incredibly costly. Computers were just beginning to be tested for business processes, and the monolithic computers were priced dearly in and of themselves. Computers were error-prone, capricious, and untrustworthy, and they were often a lone programmer's only peer for miles around. Additionally, for a programmer, their salary was next to nothing compared to the up front costs and yearly licensing charged for what seem to us now to be glorified calculators. The relatively small value of a programmer, their skills, their experience, and the perception of them as clerical workers, or worse (women!), made programmers poorly paid, and easy to replace.

Source: stanford.edu, "Researcher reveals how 'Computer Geeks' replaced 'Computer Girls'"

Decades later, businesses rely absolutely on the IT industry to keep their businesses running. Computers themselves are relatively cheap, and the computer fields are developed and highly specialized outside of being just "programmers:" there are Systems Analysts, Network Analysts, Software Developers, Software Engineers, Windows Specialists, Linux Specialists, Security Specialists, Database Administrators, Database Programmers, System Administrators, System Programmers, etc. Each specialization has its own area of expertise, its own slice of the "stack" that they manage, program, and configure. And each specialization has its own pay grades, and those pay grades are respectable compared to other science or engineering disciplines (out of college, at least, though less so as time progresses).

To qualify this better, specialization within the computer industry is absolutely necessary for individuals and businesses alike: computers are simply too complicated now to consider anything about working with them to be "clerical" (except for maybe data entry). It is rare the type of human brain with the type of infinite recall required to master any or all components to computer systems, with it being much more common to be well-versed in a handful of components. With that specialization comes years of training, education, learning, and experience to hone one's expertise, and highly skilled individuals command a higher salary. So whereas before computers themselves were by and far the majority of expense for a business' computer needs, now IT support and software development services and personnel far outweigh the cost of any hardware investment. And in my experience, nothing is more frustrating to people than expensive middle-men.

---

A small business has a problem. Its customer base is growing, and its patchwork customer database system (created, designed, and maintained by one of its employees with little formal training) is at any time one click away from imploding, with no backups, or redundancy in personnel that can manage the database. The longer it stays like this is an increasing liability, and costs ever more dearly in terms of wasted time and maintenance, and causes the business to fall further behind business partners and competitors in terms of being able to maintain accurate and useful records.

A software development firm happens to share their office building. It's the case that the firm has done work for them before in terms of basic things like email services, some desktop and application support, and the occasional "What's wrong with this?" question across the office boundaries.

The small business decides to engage the software firm to build them a replacement application for the customer database.

For what seemed like a simple problem, the development took much longer than the small business expected. On their limited budget, they hadn't imagined the process taking that long, and the funds set aside for the project were coming to an end.

Finally, as the contract ends and the money is spent, the finished application is turned over to the small business. It does what it needs to do. Basically. But it has at its core a critical flaw. As a "primer" to the application's database, a number of spreadsheets have to be fed into the system, parsed, mangled, considered, and ultimately stored in a way that is useful to the application. This priming process, however important, frequently fails. The developers of the application never tested the priming process "at scale," meaning that they only ever chose to test with a handful of records, and not a full data set. As a result, the developers never realized that running the priming process "at scale" meant that it would take upwards of four hours to complete a single spreadsheet. And there were dozens of spreadsheets.

They also never answered the question of "What if the person importing the spreadsheet is logged off?" such as would happen during mandatory system updates. In those cases, the process would fail, and start from the beginning. In fact, if for any reason the system failed to complete its process, it would start from the beginning.

Had the system contained a "batch" processing system, one that didn't rely on user interaction and could be relied on to perform its tasks on off-hours, the problem may have been tolerable. However, as it stands, the system requires somebody to babysit their computer for four hours, making sure that their computer never a) goes to sleep, b) shuts down, or c) closes its web browser.

For a small business, there is nobody who has that kind of time to dedicate, nor should they be forced to do so. The small business consults the developer on their problem. They say they didn't have enough time to do product testing, and would need quite a bit more than a quick look, as the single developer who worked on the project had left the firm.

Now, in addition to their reliance on their new application, they have an already expensive solution that now wastes more employee time than its predecessor.

The small business resolves not to do business with the development firm in the future.

---

Ideally, the members of the IT industry should be under the scrutiny of a technological meritocracy: the better you are, the more knowledgeable, or more experienced, the more reliably and efficiently you can perform a task, and the more your time should be worth. The reality, however, is much less than ideal. Trust between strangers has more to do with marketing than anything else, and in the case of small businesses seeking IT services, particularly ones without dedicated IT staff or employees knowledgeable about computers, it's a roll of the dice whether their investment is worthwhile, or the people they are working with are worth what they charge, or whether they're able to complete the project at all.

Take, for instance, a small business that ended up tracking me down in hopes that I could recover a failed hard drive. They were to some degree victims of their own apathy: they had a single computer acting as the sole store for all of their contact and appointment information, which they had been told was a bad idea. When that computer inevitably failed, they tried taking it to a number of the Apple stores in town, at each finding that none of the ones in town were equipped to deal with the drive failure, were ignorant as to the severity of the failure, and could do nothing but refer the business owner to increasingly expensive solutions.

It was only by dumb luck that one of their clients had a grandson with a degree in computer science and experience performing drive recovery. I was able to perform the recovery, get her computer software reinstalled and reloaded with her critical information, and set up an automatic backup system in hopes of making future recoveries simpler. That I was able to perform the recovery was lucky: the files on the drive were literally erasing themselves as I read them off. And for maybe a tenth of the cost of professional hard drive recovery, I was able to save her potentially hundreds of hours of work collecting her information again. I haven't heard from the business since, but I assume no news is good news.

---

For going on what I think is two years now, the TitleWave Books web site has been fairly dysfunctional. As it stands, it is a series of static pages, some giving pertinent information, some embarrassingly outdated. On the Frequently Asked Questions page, the first question is "Can I browse your inventory online?" which is answered with the same message they've had for a number of years: " We are developing a new inventory database." Essentially, no, but we're working on a new system.

At one point, the TitleWave site had a fairly impressive online inventory and ordering system, and it worked surprisingly well for a custom-made product. Ordering was simple, searching was convenient, and usually well-updated. After some time, they brought down the inventory search and ordering portion of the site because it was being redone. For a long while, the page remained the same, updated with new events and articles and content, while the search function cheerily reported that it was undergoing maintenance and would be update again sometime soon.

The page has since de-evolved from its glory days of free in-state shipping and not having to call in for book availability to its now cobbled together mess of pages. Judging from the source code, it appears straightforward, like somebody knew what they were doing, but gives away in places that it was put together by what looks like a page generation tool, and a fairly limited one at that. It's what I might put together if somebody asked me to "Just put something up, anything, so long as it says these things, and maybe has a few pictures."

I was curious about this a while ago. I even sent in an email to their information email inbox (to which I received no reply). I started searching around. What I found was somebody who claimed to be the developer for TitleWave, listing it on their profile on a professional social network. They had since departed TitleWave, moving on to other opportunities in the lower 48, approximately around the same time as when thing started to regress.

I don't really know anything about the situation, but I can guess. The first possibility is that the original developer hadn't produced something that the client was happy with, even though it met its basic requirements. If this was the case, then for the additional work to complete the project, the developer may have requested more money, or at least some compensation for the extra time it would take to complete the project. A disagreement on this may have caused the developer to leave.

It may also have been just a parting of paths. The developer may have found other opportunities, decided to end his work with TitleWave, and move on. If he indeed worked alone, it may have been the case that he left an indecipherable pile of code and mess for the next person (maybe even the business owner). Or it may have been that he left things in a reasonable state, with good documentation, but there was still nobody around to maintain the system. When something broke, it broke for good, until the "new inventory database" rolled around.

Whatever the case may be, it's unfortunate that the result left TitleWave in such a poor state. I don't have enough information to come to a logical conclusion about what happened with their site, but my gut feeling is that they somehow got screwed.

---

In my experience, the "laying of hands" situation is what people hope for, but rarely ever find: that somebody with a computer problem, either personal or business-related, can fix their problem with relative ease, and if not, be able to fix their problem at all, and if not, be honest about it. And yet being repeatedly disappointed by, taken advantage of, or simply being charged unreasonably leads to further distrust of the IT industry.

So we have our own track record to blame. But also to some degree our "geek" stereotype. Popular culture continues to portray the IT industry as "computer people," stereotypically anti-social, awkward, introverted, and homogeneously male. Shows like "Chuck" or "The IT Crowd" or "Big Bang Theory" poke fun at the geek stereotype and have a cast of mostly male characters playing the geek roles. There are shows with the stereotype present in female characters ("24" and "Firefly" are the two that come to mind), but they are in the relative minority.

Why would people distrust a geek, even if they might be the only hope in solving a problem?

This is where I wander back to thinking about the vanishing numbers of women in the IT industry. And it brings me to the question: What group, real, fictional, stereotypical, or otherwise, consists of an overwhelming majority of men, either traditionally, culturally, or coincidentally, and that most people (or just you) trust that group implicitly?

I'm having trouble thinking of any. I would guess doctors (70% male) would garner some level of trust, but certainly not implicit trust (there is such a thing as malpractice, after all). I can much more easily name mostly-male groups that people don't trust implicitly: politicians, priests, Wall Street, professional sports teams, corporate executives, the homeless, prison inmates, alcoholics, drug addicts... erm, the armies of Mordor?

I know. The association is tenuous at best. There's no way I can get away with saying that because some groups are distrusted it's because they're male, and I definitely can't get away with saying that that is one of the main reasons for why people may distrust the geek stereotype (if indeed they do distrust them at all). But it's something to think about. Would you trust your local computer person more or less if they were female? What if the Best Buy Geek Squad consisted only of women?

---

What sparked this discussion was a thought I had. I was thinking about what it would be like to teach programming to students: whether I would enjoy it, whether I would be any good at it. My experience so far in teaching people about programming has been somewhat mixed, and with questionable bias: the people I was teaching at the time were either being paid to learn, or were forced to seek my help due to the classes they were taking.

I was also thinking about how best I learned when I first started out. It seems like I've always had a project, or some small and interesting thing to keep me occupied for a time, and it was always in trying to solve problems in and around those things that made me any better at programming.

I was also thinking how pointless my various internships were. Well, I should say mostly pointless: I did still learn a lot, if not about programming and computers, but learning how to work with people, and at times I would even get a brief glimpse of the big picture for projects, or get to see how things were "really done." The reason I say they were pointless is because I would still go home and work on idkfa (or work on idkfa at work while bored). My personal projects were always much more exciting than what I was doing at work.

The drawback to spending so much time on my personal projects is that I had no direction on them. Without direction, I slowly produced the mess that was the idkfa v2 codebase, and the rest of the side-projects I developed before and throughout college. Granted, I learned (slowly) from my mistakes, and made efforts to correct them at various points, but it was usually the case that by the time I figured out the right way to do something, it was already too late in the game to do things right.

In thinking about these things, I was also trying to decide at what point I would have been useful to businesses like those whose problems I've detailed here. Arrogance says maybe after high school. Reason says maybe after college. Wisdom would probably say that we're lucky these things work at all.

So the thought I had was for a mentorship that focused on helping small businesses solve their more difficult, "custom" problems. They would be problems that involved sufficiently complex solutions, such that those doing the programming would have to experience many pieces of the puzzle in order for things to work. The mentor would be an IT professional, with hopefully years of experience, and a proven track record of talent and expertise in their careers, and would be looking to donate their time. The mentees would be students looking to gain real-world experience solving problems, but also in working with clients and seeing the process in its entirety rather than just being hired on to do "the database work" or "the reporting."

The mentee would be paid a minimal hourly wage, and the mentor would donate their time and expertise for free. The mentee would be paid to make the time spent on the project worthwhile, but also to ensure that the client businesses didn't abuse the time of those participating in the mentorship. The mentor's job would be to supervise the project, give structure and direction, introduce the participant to the "right way" about things, and help manage the relationship with the business in need.

Small businesses would enter their projects into a lottery, and depending on personnel availability, have a chance to have their project worked. The program would review each project request to estimate difficulty, complexity, and necessity, and choose from the pool which projects to unleash the students upon.

Ideally, the project would be worked to completion, and at the very least to a point of satisfaction to the customer. Additionally, one of the stipulations of generating this work would be to ensure that any work done would be well-documented, well-tested, and be immediately maintainable and reusable by the client if need be.

I understand that similar programs exist. I think that the University of Alaska has a community outreach program for its engineering programs, as well as an intern placement program for some of its computer science students. These succeed, to some degree, but tend to place the interns in situations where they have the worst or most menial portions of a project, or have little input or creativity when it comes to participating, or simply don't have enough time to see something accomplished. Having the mentor as a resource, as well as placing the participant in a pivotal role for the project, would be much more beneficial to the participant in my opinion.

The mentorship would also add a more personal element to the instruction and learning. If the "geek" stereotype applies at all well to the IT industry, we exhibit anti-social and introverted tendencies, and this is potentially reflected in how we interact with our classes. Personally, it was only ever me, my text editor, and a compiler, trying to wrangle some project or exercise emailed to us by our professors. My higher education experience was not a social one, even though I may have benefitted from having more lab partners, or even talking to a single professor or TA. I still learned the material, but I may have learned it faster with somebody telling me, showing me exactly what I needed to know (computers being the "oral tradition" that they are).

I like the idea. But the problem would be trust. From a business perspective, trusting your critical business systems to a student, an apprentice, would be risky. Most businesses would prefer to simply pay the mentor for their time and be done with it. The system would have to be proven, such that businesses felt they could trust the program, even if a novice was doing the majority of the work. It would also have to be the case that the mentor trusted the mentee to do the work per instruction, but also respect their ability to perform the task.

Were this kind of program to exist, and be a trusted and celebrated way for small businesses to better solve their computer problems, it would be an interesting thing. It would be similar to the Google Summer of Code project, but instead of having students participate in open source software projects, their time would be spent trying to improve upon businesses in their community. It wouldn't necessarily help with failed hard drives, and it wouldn't be guaranteed to produce the best of products.

It would, however, make information technology and programming more approachable, less opaque, and more engaging, professionally, academically, or otherwise. It would also take steps to proving that computer industry doesn't consist entirely of overpaid middle-men, and also potentially better disseminate the computer expertise that seems to be constantly in short supply.

Were this system to exist, I might be a mentor.

- Previous: Everything in Moderation

- Next: Drowning